There’s been bad news for billionaires in the news business lately.

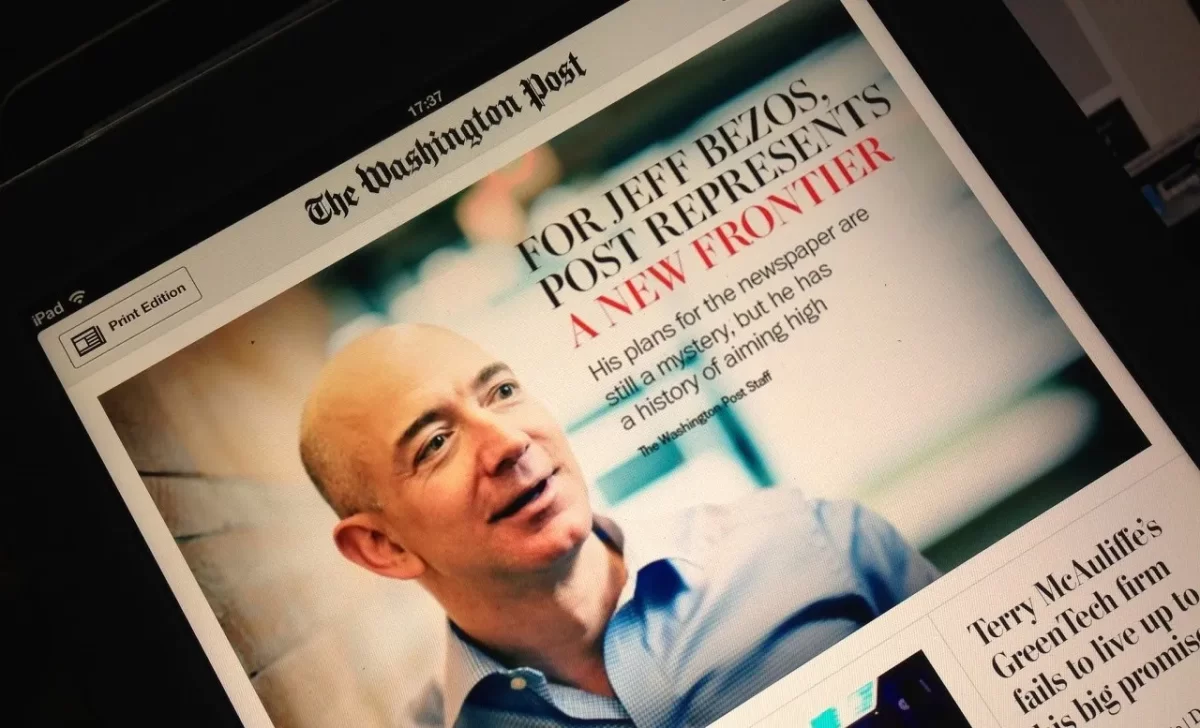

Just over a decade after Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post for $250 million, the venerable paper is losing $100 million a year. Other big outlets scooped up by deep-pocketed media outsiders aren’t faring much better.

The Los Angeles Times, which biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong bought in 2018, loses an estimated $50 million a year, and is in crisis following the recent, abrupt departure of its editor-in-chief and two of his top deputies. Time, acquired by Salesforce founder Marc Benioff in 2018, announced layoffs late last month in yet another round of cost-cutting.

Plutocrats may not be the old media saviors they were briefly hyped to be. That hype was always tempered by consternation around billionaire meddling in the Fourth Estate. But the financial lifeline they provided, and the protection against subsumption by private equity funds or faraway telecom conglomerates, outweighed the risks.

What went wrong?

Times changed, quickly, after Bezos’ shock purchase of the Post. The media outlook was no doubt grim in 2013. Legacy outlets were still recovering from the financial crisis and attendant freefall in advertising, which prompted The Atlantic to posit in 2009 that the New York Times might shutter by the end of that year. Digitalization raised the threat to existential proportions as the old guard lagged in figuring out how to make money online.

Yet young platforms like Buzzfeed, Vice and Gawker Media were booming. Crucially, veteran and upstart publishers alike saw a lift from their content being widely shared on social media as it exploded in popularity. This left the media at the mercy of tech companies and their constantly shifting algorithms, but it also had the potential to make news content go viral at a previously unimaginable scale.

In that context, Bezos had reason to be optimistic. Likewise Soon-Schiong and Benioff, who made their buys following another media inflection point of the ‘10s: the Trump Bump.

There was atoning by news outlets when Trump took the White House for the outsized attention they lavished on him in 2016,, but the boon to the bottom line that drove those decisions continued throughout his presidency. When the NYT debuted its “The Truth Is Hard” ad campaign during the 2017 Academy Awards, it reportedly gained more new subscribers in 24 hours than it had in the previous six weeks. The number of digital-only subscribers to the NYT and the Post tripled between 2016 and 2020 as readers sought to process the daily chaos unfolding in Washington and, perhaps, support a free press under attack by the president.

Now, as we hurtle towards a Biden-Trump rematch, Benioff, Bezos and Soon-Schiong confront the US media in what may be its deepest trouble yet.

Two recent developments,combined with persistently dwindling ad revenues, have brought us here.

Firstly, social media companies have pumped the brakes on news content that appears on their platforms. Between 2021 and 2022, traffic sent to publishers from Facebook plunged 48% and, from X, 27%. News currently constitutes just 3% of what people see across Meta platforms.

A sector-wide rush to video content and the fear of reputational damage for spreading dangerous misinformation are two reasons for this. A third are the soured relations between the media and Big Tech following intense drives by publishers to be compensated for the traffic their journalistic work drives to Facebook and the like.

Secondly, the seemingly bottomless well of dire news since 2016 has led to fatigue among media consumers–and dimmed hopes of a Trump Bump redux. The share of Americans who closely followed the news fell from 51% to 38% between 2016 and 2022, according to Pew Research Center. Cable news ratings were down between 30 and 55% for early primary coverage this year versus 2016.

Blame for these problems can’t be squarely laid on the tech titans running major outlets. After all, they same issues are plaguing news orgs across the board, leading to a rethinking of subscription models as readers wince at growing bills, aggressive newsletter marketing, and the hope of replicating the NYT’s winning (so far) gamble on charging separately for access to news, sports, cooking and word games.

Still, the perception of aloof leadership by uber-rich media interlopers in a time of crisis is corrosive. Bezos, so often shuttling between star-studded bashes in Miami and Beverly Hills, does not seem particularly focused on his DC news outlet. And David Smith, the ex-Sinclair Media chief, telling staffers at his newly purchased Baltimore Sun that he hadn’t read the paper in four months didn’t jolt confidence.

Then there’s the matter of unethical billionaire intervention. This contributed to the LA Times’ current plight after Soon-Shiong attempted to kill a story about his friend and fellow billionaire Gary Michelson being sued by a woman his dog allegedly attacked.

But the main problem is that the foundational shift taking place across the media overpowers even the deepest pockets. And that the extremely wealthy won’t tolerate losses for long.

A version of this article previously ran in Hearst’s Connecticut Media Group publications.